To Contain the Uncontainable

A photojournal from the mosques of Turkiye to the hills of Devon, England

by Karim Wadhwani

July 11, 2025

The semazen whirled like a planet around the room in front of me. Dressed in a white cloak and a tall, auburn hat, he rotated elegantly - one foot to the earth, briefly, and then the other, with grace like that of an experienced swimmer, barely making ripples in the water.

The powder under his feet - meant to create friction and prevent slipping during the hour-long dance - scattered, turn after turn, until it became an image of the Sufi’s dance, memorializing his movements.

It made me think of the undulating landscapes of Cappadocia we had seen a few days earlier. There, deep expanses of time are etched in rock - millions of years of volcanic flow and erosion by wind and water have created an environment alien to this awestruck North American. Layers of ash and sediment sculpted into canyons and valleys, and the distinctive hoodoos or “fairy chimneys”.

People lived and worshipped here, carving the stone into churches, monasteries, and homes. In an environment formed by movement at a scale that our everyday human experience can barely fathom. But we can reflect on its image, the land.

Space for Light

I’ve been thinking a lot about images lately, not least because I practice photography.

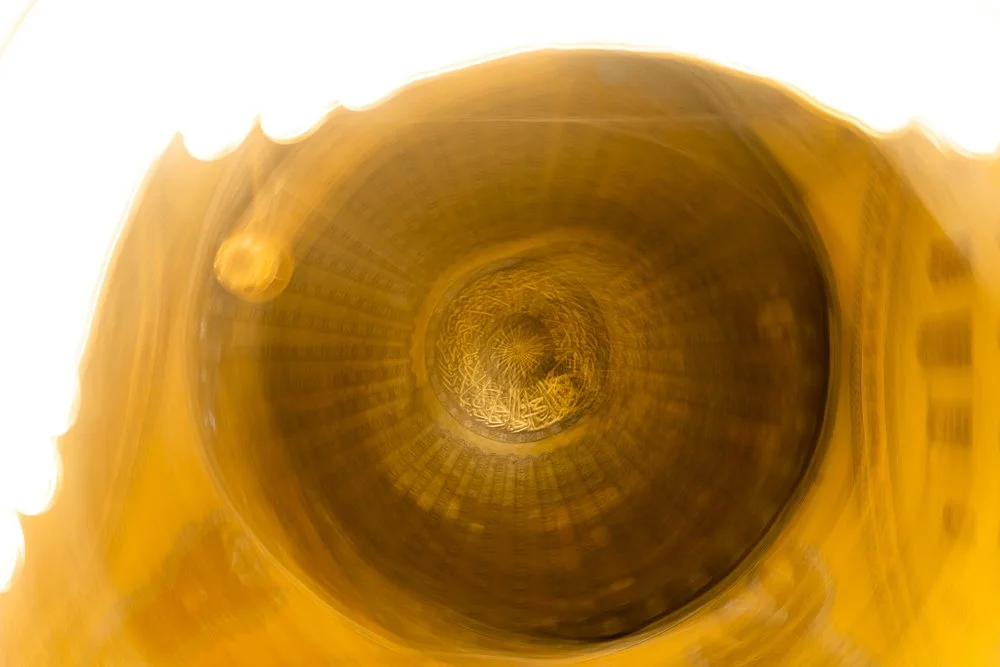

A photograph, like the scattered dust under the semazen’s feet or the hoodoo housing a Byzantine church, is also an image of movement. Not in the sense that it “freezes” an object that was previously moving, which is how we colloquially understand it, but more that the photo is moved by the subject; it too is part of the dance. Like the fields outside Goreme, eroded by wind and water, a photograph is also a landscape - shaped by light erosion.

An analog photograph is made when photons enter the camera through a lens and hit the surface of a gelatin emulsion containing silver halides. Each photon that hits a particle of silver halide transforms it - into silver. The lighter parts of the scene being photographed correspond to larger clusters of silver, and the darker parts remain mostly halide. The result is a latent image mirroring the scene, an image that our eyes can not see (and requires processing in the dark room) but nevertheless exists, a record of all the photons that bounced off that beautiful building or loved one you saw through the viewfinder. This is alchemy. Byung-Chul Han, the German philosopher of Korean descent, says “it has something to do with resurrection”.

Digital photography is different. It does not work by the same physical process, and Han critiques it as ——. But my view, having devoted much of my life to digital photography, is that it is no less a magical and alchemical craft. Firstly, the digital is not divorced from the physical. It is all made of the same stuff - computers and phones and DSLR cameras are made of the same minerals and materials as other human tools, including those used in making art. The difference is that their physicality is obfuscated from us - cables that carry the signals that make the Internet are buried in the deep sea, our files are stored in the “cloud” but really in behemoth warehouses all around the world, and so on. And all of it - including both iPhones and paintbrushes - has as its essential building block stardust. This is poetic but quite literally true as well.

And so an instrument made of minerals flung by distant stars to earth, shaped by human and robotic hands into a mirrorless camera the result of thousands of years of tinkering and exploring optics, now sits in my hands. I click the shutter button and the photons bouncing all around me - stardust - enter the chamber of darkness. The sensor makes sense of it all, and the camera, which is really a computer, organizes it into something readable by my laptop computer when I plug it in later at night.

[photo of Dada - photographer unknown]

- and in the case of analog photography - actually continues the movement of the subject. Let me explain. Photons

***

Presently, the Sufi practitioner continues his soft turns. Their dance is the sema, which means to listen, and they are semazen - listeners.

This question was central on my journey - what might we hear if we listen? Not in the listening of our daily experience, but in deep-time listening.

Photography, listening, spiritual practice, these are all concerned with receiving - whether it’s light, sound, or awareness.

physical light, the light of awareness, and divine Light, respectively.

And receiving requires receptivity - a space conducive for it. The retreat in Devon was all about this - how can we make space, in our gatherings, our communities, and firstly in ourselves, to receive Her.

To even put those concepts (physical, intellectual, and divine light) as distinct categories feels wrong. Dichotomies, categories, boxes - these are spaces we create to make sense of what’s ultimately ineffable. An attempt to contain the uncontainable. Our teacher, Emmanuel, spoke much about porousness. For the vessel to contain some water, it needs sturdy walls. But for the vessel to become water, its walls, which are its vesselness, must dissolve.

In the end there is nothing but all, at once. The hoodoo tells me of the wind that touched her, the photograph tells me of the “treasury of light” that emanated from my nephew’s smile, and so too does the whirling dervish tell me of the unseen.

All of it, here, now, One.

The whirling dervish spins out of the everyday experience and into another realm. Or do they? Language can introduce dichotomies that, while being helpful when first introduced to a new concept, can detract from a deeper understanding. Having witnessed their ceremony, I would rephrase that they open up a space - they aren’t

—-

somewhere in the retreat’s greenness I realize that photography is, for me, a spiritual practice. And then I realize that’s not such a remarkable thing to realize. All art can be this, for the artist, regardless of the language one chooses to employ.

***

Tiny insects crawl over my laptop keys as I write this piece. It’s July in Toronto - one of three months in the year when we don’t need jackets, for now - and I’m sitting under the shade of a tree outside a library.