To Contain the Uncontainable

A photographic journey through ritual, landscape, and stillness — from Istanbul to Devon

by Karim Wadhwani

July 11, 2025

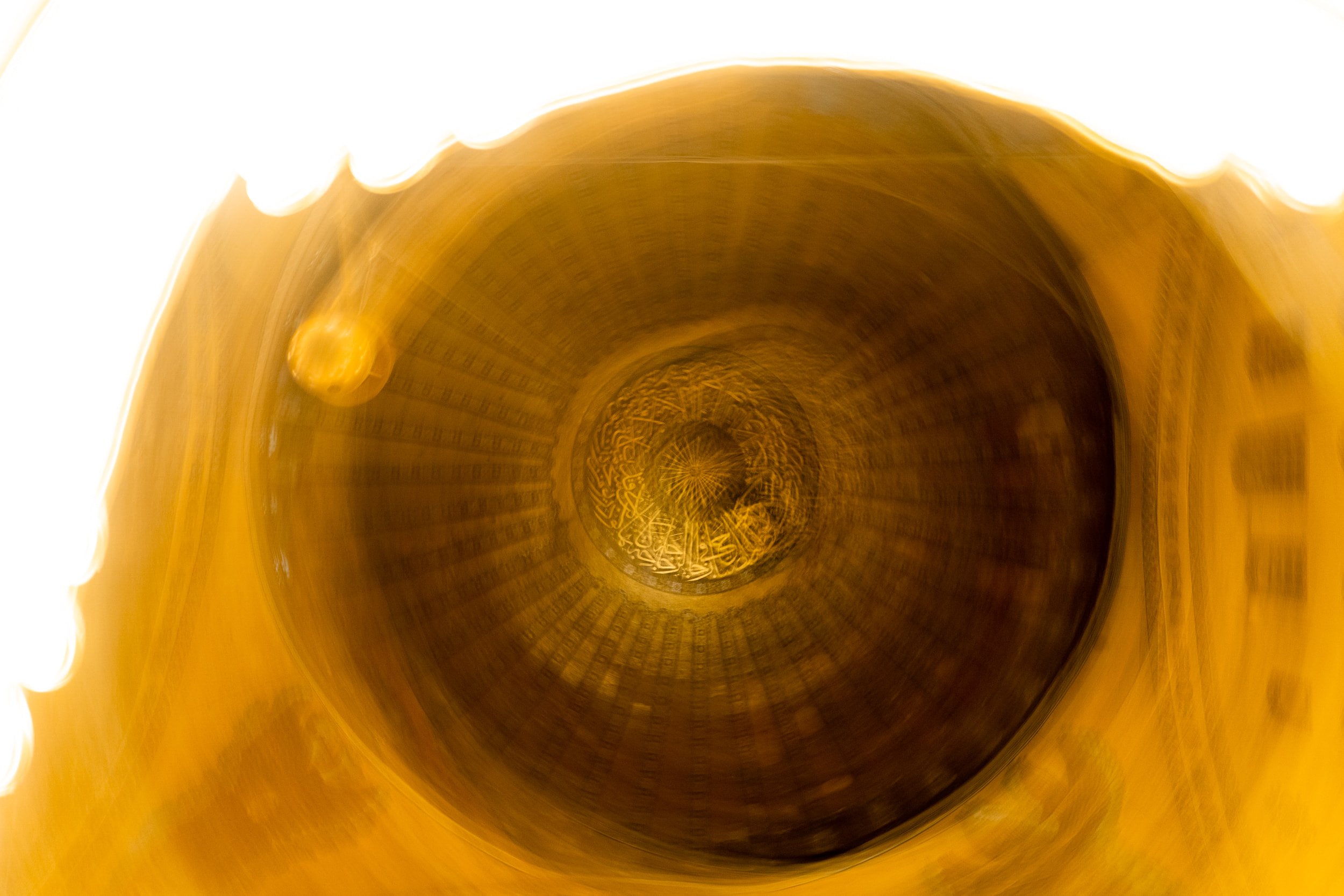

A Space for Listening | Istanbul

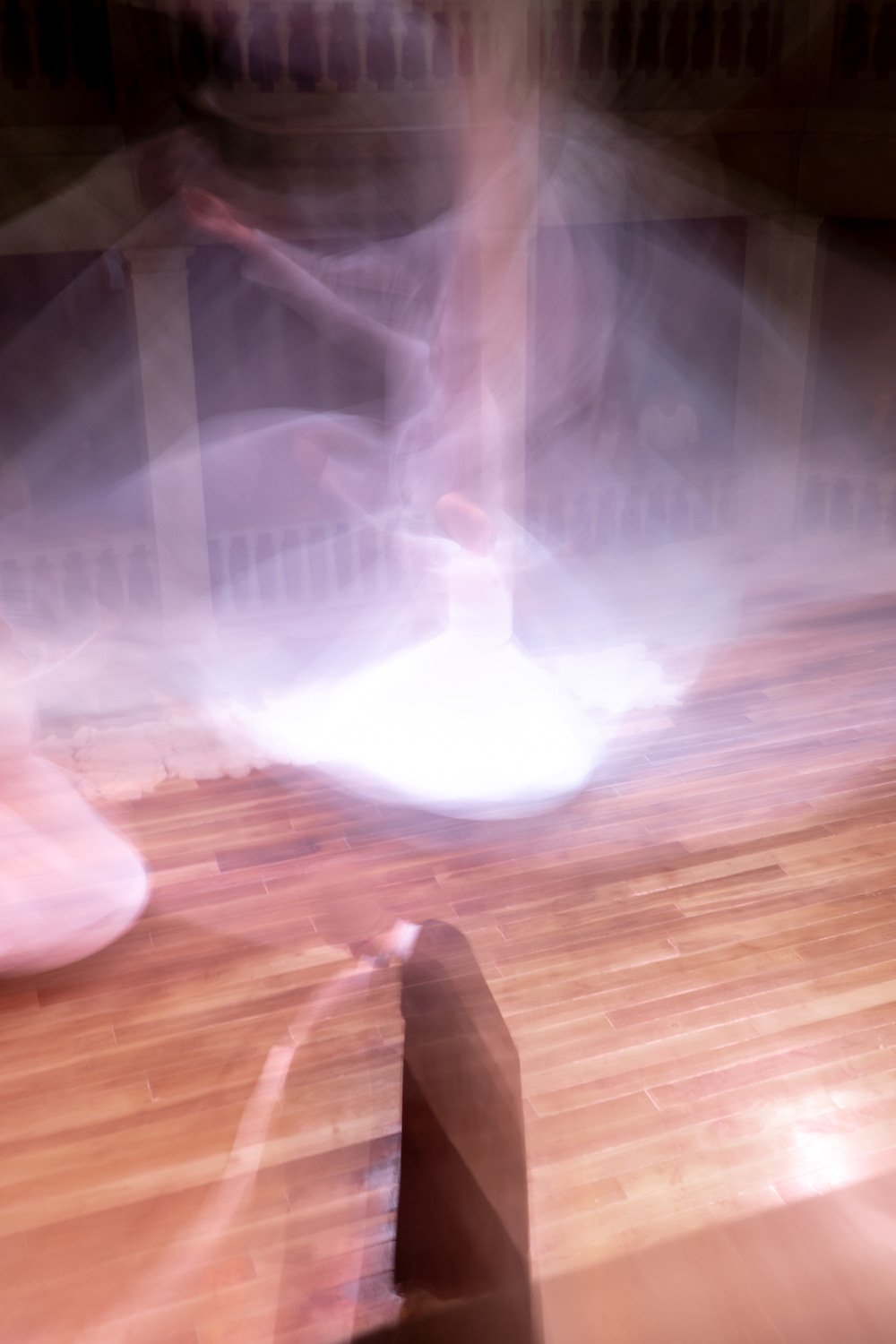

The semazen whirled like a planet around the room in front of me. Dressed in a white cloak and a tall, auburn hat, he rotated elegantly - one foot to the earth, briefly, and then the other, with grace like that of an experienced swimmer, barely making ripples in the water.

The powder under his feet - meant to create friction and prevent slipping during the hour-long ritual - scattered, turn after turn, until it became an image of the sufi’s dance, memorializing his movements.

It was June and I was in Istanbul visiting the Mevlevi sufi lodge in the Kasimpasa district. Our taxi had climbed at almost a 45 degree angle up a narrow cobbled street to the gates of the complex. We continued the climb on foot up to the main courtyard where we took refuge from the afternoon sun under trees and umbrellas. The courtyard was enclosed by various buildings in Ottoman architectural style hosting traditional arts classes, a gift shop, and the semahane, the space where the ritual would take place.

After my third cup of Turkish çay (tea) of the day, we filed into the two-storey building housing the semahane. Inside, the space was octagonal, with columns and vaults supporting a double-height ceiling. There was a calm in this space and we talked in whispers as we eagerly awaited the ceremony.

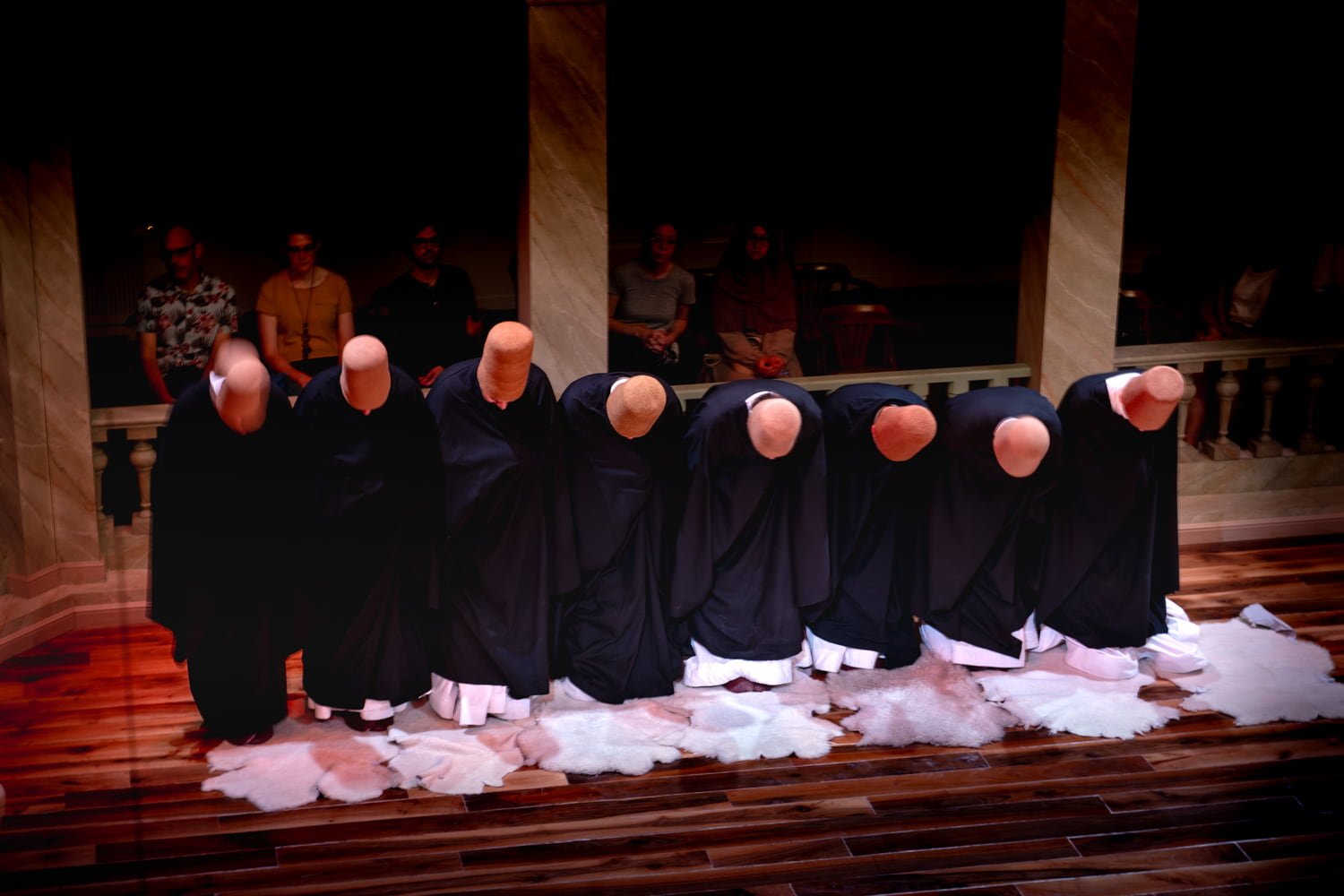

The members of the sufi tariqah (spiritual path or order) appeared, 8 men wrapped in black cloaks. They bowed as they sat on furs awaiting them on the wooden floor. The rhythm and flow with which they moved as a collective, before the whirling even began, reminded me of leaves on a tree branch, or vertebrae on a spinal column. Each one distinct yet connected by a larger purpose.

The ceremony is called sema, which means to listen, and I reflected on the idea that those who practiced it are called semazen, literally those who do sema — listeners.

The ceremony is a spiritual practice, a ritual of listening. As the semazen removed their black cloaks, revealing white cloaks underneath, the sound of a reed flute pierced the silence from above. A group of musicians sat on the second floor gallery, accompanying the dervishes below in this unfolding practice.

The ceremony had several stages

These stages can teach us, in ritual form, about the journey of a seeker as she walks a path of seeking. With all its messiness and order, dynamism and stillness. Of dissolving and becoming, again and again.

I wanted to use photography to express these ideas, so that the photo is not a snapshot of a moment removed from its context, but a record of the dance, the movement, the traces of light in which that moment took place.

The Land Remembers | Goreme, Cappadocia, Turkiye

The scattered dust under the sufi’s feet and the traces of the sema movement in my photos made me think of the undulating landscapes of Cappadocia we had seen a few days earlier. I realized the landscape too is a kind of image of movement.

There, deep expanses of time are etched in rock - millions of years of volcanic flow and erosion by wind and water have created an environment alien to this awestruck North American. Layers of ash and sediment sculpted into canyons and valleys, and the distinctive hoodoos or “fairy chimneys”.

People lived and worshipped here, carving the stone into churches, monasteries, and homes. In an environment formed by movement at a scale that our everyday human experience can barely fathom. But we can reflect on time’s image, the land.

We were in Goreme for 4 nights, and each morning before the dawn we gathered in the chill on the rooftop of our hotel. A different ritual was about to unfold, a different sort of dance.

Flying on hot air balloons across this landscape has become a popular tourist draw.

My daily rhythm was different here, aligned to both the modern balloon ritual and the ancient arid environment: stay up all night when it’s cool, witness or take part in the balloon procession, nap during the 40+ degrees heat, and hit the markets in the late afternoon.

Listeners, cultivating presence through remembrance of the divine. Here a question formed and became central on my journey: what might we hear if we listen? Not in the listening of our daily experience, but in deep-time listening. How can we prepare space that is conducive —

These are all single exposures taken in camera. No Photoshop or AI used.

And it required a space conducive

and as soon as we entered the space in the Kasimpasa district of Istanbul it felt dignified and serene. It isn’t a performance, but a space and ritual where presence is cultivated through remembrance of the divine.

As visitors we sat around the perimeter of the room.

Presently, the Sufi practitioner continues his soft turns. Their dance is the sema, which means to listen, and they are semazen - listeners.

This question was central on my journey - what might we hear if we listen? Not in the listening of our daily experience, but in deep-time listening. How can we prepare space that is conducive —

Photography, listening, spiritual practice, these are all concerned with receiving - whether it’s light, sound, or awareness.

Popularly known as whirling dervishes, the practice has become a tourist attraction, and one can even find it packaged with dinner cruises on the Bhosphorus river which separates the European and Asian sides of Istanbul.

However there are still a few traditional spaces where the ceremony is conducted with dignity and serenity in a spiritual gathering.

I was in Turkiye as a side quest - the main purpose of my trip across the Atlantic was to attend a spiritual ecology workshop on the rolling hills of Devon, UK. Like any reasonable Canadian, I wanted to package this skip over the pond with another place to visit, to maximize the opportunity (and help make the price tag a bit more bareable). After considering a few options, Turkiye (recently renamed from Turkey) won.

Our first stop was the town of Goreme, in the Cappadocia region. This is the area now famous for hot air balloon rides over its majestic valleys.

Contrast this deep-time with the seeming precariousness of hot air balloons. Yet it’s similar elements that make that journey

How can I express the movement, the dance, of hot air balloons over Goreme? My humble attempts involve using a slow shutter speed to capture the trails of these vessels over a longer period, memorializing their dance like the powder did, however fleetingly, for the sema.

All of these images are made with conscious hands. The images of the balloons taking flight come through my camera,

The landscape, too, is made by conscious hands. DUring the Seeds course there was much discussion of the Earth as a living being. A profoundly mysterious one, but a living one. And so the landscape isn’t just an accident of inert matter interacting with other inert matter, but the result of (and a part of) a living, divine being. Made by it, made by Her, as Emmanuel would say.

Thinking of the earth as a living presence creates a shift. Ecology is infused with deeper love, reverence, mystery. Sam Lee quoted often that in order to protect something, you must love it first. I remember hearing a similar sentiment from Prince Hussain Aga Khan

In mystical traditions, the cosmos is considered a theophany (Arabic: tajalli), an unveiling of the divine mystery in the forms we can see and experience. These include us, as well as the more-than-human intelligences and beings around us.

Space for Light

I’ve been thinking a lot about images lately, not least because I practice photography.

A photograph, like the scattered dust under the semazen’s feet or the hoodoo housing a Byzantine church, is also an image of movement. Not in the sense that it “freezes” an object that was previously moving, which is how we colloquially understand it, but more that the photo is moved by the subject; it too is part of the dance. Like the fields outside Goreme, eroded by wind and water, a photograph is also a landscape - shaped by light erosion.

An analog photograph is made when photons enter the camera through a lens and hit the surface of a gelatin emulsion containing silver halides. Each photon that hits a particle of silver halide transforms it - into silver. The lighter parts of the scene being photographed correspond to larger clusters of silver, and the darker parts remain mostly halide. The result is a latent image mirroring the scene, an image that our eyes can not see (and requires processing in the dark room) but nevertheless exists, a record of all the photons that bounced off that beautiful building or loved one you saw through the viewfinder. This is alchemy. Byung-Chul Han, the German philosopher of Korean descent, says “it has something to do with resurrection”.

Digital photography is different. It does not work by the same physical process, and Han critiques it as ——. But my view, having devoted much of my life to digital photography, is that it is no less a magical and alchemical craft. Firstly, the digital is not divorced from the physical. It is all made of the same stuff - computers and phones and DSLR cameras are made of the same minerals and materials as other human tools, including those used in making art. The difference is that their physicality is obfuscated from us - cables that carry the signals that make the Internet are buried in the deep sea, our files are stored in the “cloud” but really in behemoth warehouses all around the world, and so on. And all of it - including both iPhones and paintbrushes - has as its essential building block stardust. This is poetic but quite literally true as well.

And so an instrument made of minerals flung by distant stars to earth, shaped by human and robotic hands into a mirrorless camera the result of thousands of years of tinkering and exploring optics, now sits in my hands. I click the shutter button and the photons bouncing all around me - stardust - enter the chamber of darkness. The sensor makes sense of it all, and the camera, which is really a computer, organizes it into something readable by my laptop computer when I plug it in later at night.

[photo of Dada - photographer unknown]

- and in the case of analog photography - actually continues the movement of the subject. Let me explain. Photons

***

Presently, the Sufi practitioner continues his soft turns. Their dance is the sema, which means to listen, and they are semazen - listeners.

This question was central on my journey - what might we hear if we listen? Not in the listening of our daily experience, but in deep-time listening.

Photography, listening, spiritual practice, these are all concerned with receiving - whether it’s light, sound, or awareness.

physical light, the light of awareness, and divine Light, respectively.

And receiving requires receptivity - a space conducive for it. The retreat in Devon was all about this - how can we make space, in our gatherings, our communities, and firstly in ourselves, to receive Her.

To even put those concepts (physical, intellectual, and divine light) as distinct categories feels wrong. Dichotomies, categories, boxes - these are spaces we create to make sense of what’s ultimately ineffable. An attempt to contain the uncontainable. Our teacher, Emmanuel, spoke much about porousness. For the vessel to contain some water, it needs sturdy walls. But for the vessel to truly know water, it must become water, and to become water its walls, which are its vesselness, its subjective point of view, must dissolve.

In the end there is nothing but all, at once. The hoodoo tells me of the wind that touched her, the photograph tells me of the “treasury of light” that emanated from my nephew’s smile, and so too does the whirling dervish tell me of the unseen.

The hoodoo tells me of the wind that touched her, the photograph of my grandfather tells me of the “treasury of light” that came from the sun and was transfigured by his face, and so too does the whirling dervish tell me of the unseen.

The hoodoo tells me of the winds that shaped it, the whirling dervish tell me of the unseen, and the photograph of my grandfather tells me of the “treasury of light” that came from the sun that day, to be transfigured by his face.

All of it, here, now, One.

The whirling dervish spins out of the everyday experience and into another realm. Or do they? Language can introduce dichotomies that, while being helpful when first introduced to a new concept, can detract from a deeper understanding. Having witnessed their ceremony, I would rephrase that they open up a space - they aren’t

—-

somewhere in the retreat’s greenness I realize that photography is, for me, a spiritual practice. And then I realize that’s not such a remarkable thing to realize. All art can be this, for the artist, regardless of the language one chooses to employ.

***

Tiny insects crawl over my laptop keys as I write this piece. It’s July in Toronto - one of three months in the year when we don’t need jackets, for now - and I’m sitting under the shade of a tree outside a library.